Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and the American Library in Paris

In the closing years of World War I, 1917-1918, hundreds of American libraries, under an initiative of the American Library Association (ALA), launched the Library War Service, a project to send books to the doughboys fighting in the trenches. By the Armistice, nearly a million and a half books had been shipped to Europe.

(edited from a ‘Detailed History’ by American Library in Paris staff)

In the closing years of World War I, 1917-1918, hundreds of American libraries, under an initiative of the American Library Association (ALA), launched the Library War Service, a project to send books to the doughboys fighting in the trenches. By the Armistice, nearly a million and a half books had been shipped to Europe.

The American Library in Paris was founded in 1920 by the ALA with a core collection of those wartime books and a motto about the spirit of its creation: Atrum post bellum, ex libris lux: After the darkness of war, the light of books. The library’s charter promised to bring the best of American literature and culture, and library science, to readers in France. It soon found an imposing home at 10, rue de l’Elysée, the palatial former residence of the Papal Nuncio.

The leadership of the early Library was composed of a small group of American expatriates, notably Charles Seeger, father of the young American poet Alan Seeger ("I have a rendezvous with Death"), who died in the war, and great-uncle of folk singer Pete Seeger. Expatriate American author Edith Wharton was among the first trustees of the Library.

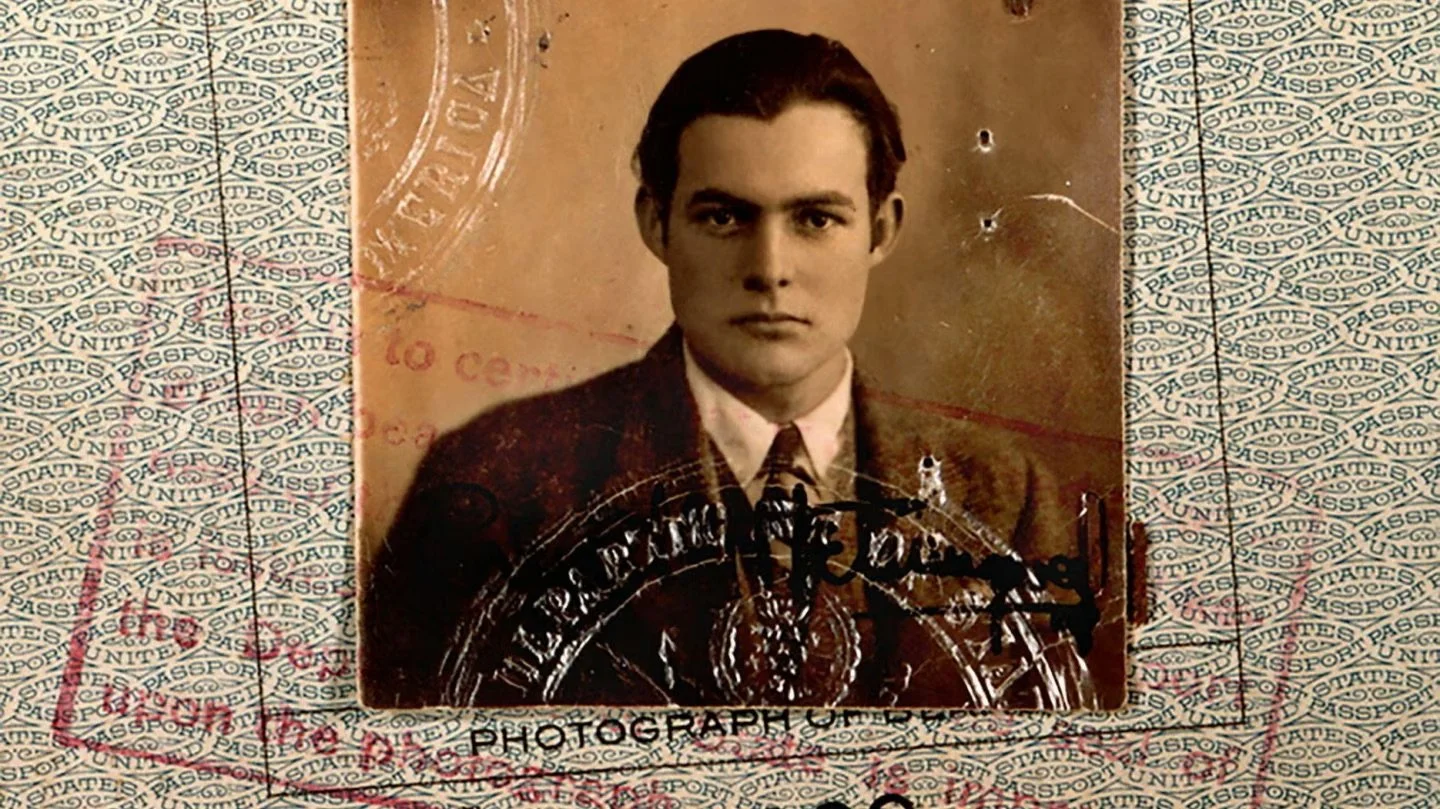

Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein, early patrons of the Library, contributed articles to the Library’s periodical, Ex Libris, established in 1923 and which is still published today as a newsletter. In a letter dated January 28, 1925 from Schruns, Austria, Hemingway writes to his Upper Michigan friend, Bill Smith, about a possible secretarial position with Dr. W. Dawson Johnston, Director of the American Library in Paris to help get Ex Libris and a book column Johnston wrote for the Paris Tribune out each month. Smith did come to Paris that spring and stayed until September but never worked at the Library

Thornton Wilder and Archibald MacLeish borrowed books from the American Library. Stephen Vincent Benét wrote "John Brown’s Body" (1928) at the Library. Sylvia Beach donated books from her lending library when she closed Shakespeare & Co. in 1941.

The Library’s continuing role as a bridge between the United States and France was apparent from the beginning. The French president, Raymond Poincaré, and with French military leaders including Joffre, Foch, and Lyautey, were present when the Library was formally inaugurated. An early chairman of the board was Clara Longworth de Chambrun, member of a prominent Cincinnati family and sister of the U.S. Speaker of the House of Representatives, Nicholas Longworth.

A succession of talented American librarians directed the Library through the difficult years of the Depression, when the first evening author programs drew such French literary luminaries as André Gide, André Maurois, Princess Bonaparte, and Colette for readings. Financial difficulties ultimately drove the Library to new premises on the rue de Téhéran in 1936.

With the coming of World War II, the occupation of France by the Nazi regime, and the deepening threats to French Jews, Library director Dorothy Reeder and her staff and volunteers provided heroic service by operating an underground, and potentially dangerous, book-lending service to Jewish members barred from libraries. Dorothy Reeder reminded staff and patrons that The American Library in Paris was a “war baby, born out of that vast number of books sent to the A. E. F. (American Expeditionary Force) by the American Library Association in the last war. When hostilities ceased, it embarked on a new mission, and has served as a memorial to the American soldiers for whom it has been established.”

When Reeder was sent home for her safety, Countess de Chambrun rose to the occasion to lead the Library. In a classic Occupation paradox, the happenstance of her son’s marriage to the daughter of the Vichy prime minister, Pierre Laval, ensured the Library a friend in high places, and a near-exclusive right to keep its doors open and its collections largely uncensored throughout the war. A French diplomat later said the Library had been to occupied Paris "an open window on the free world."

The Library prospered again in the postwar era as the United States took on a new role in the world, the expatriate community in Paris experienced regeneration, and a new wave of American writers came to Paris - and to the Library. Irwin Shaw, James Jones, Mary McCarthy, Art Buchwald, Richard Wright, and Samuel Beckett were active members during a heady period of growth and expansion. During these early Cold War years, American government funds made possible the establishment of a dozen provincial branches of the American Library in Paris, even one in the Latin Quarter. The Library moved to the Champs-Elysées in 1952. It was at that address that Director Ian Forbes Fraser barred the door to a high-profile visit from Roy Cohn and David Schine, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s notorious staff members, who were touring Europe in search of "red" books in American libraries.

The Library purchased its current premises, two blocks from the Seine and two blocks from the Eiffel Tower, in 1965 - making way on the Champs Elysées for the Publicis monument, Le Drugstore. On the rue du Général Camou, the Library helped to nurture the growth of the American College of Paris’s fledgling library. Today, as part of the American University in Paris, that library is our neighbor and tenant. The branch libraries ended their connections to the American Library in Paris in the 1990s; three survive under new local partnerships.

By the time of its 75th anniversary, in 1995, the Library’s membership had grown to 2,000. The premises were renovated in the late 1990s, and are undergoing regular updates. In 2009, the reading room was expanded and new audio-visual equipment was installed for programming. The American Library in Paris remains the largest English-language lending library on the European continent.

This article was orignally published in the Hemingway Foundation Spring 2014 Dispatch

HEMINGWAY EXPELLED FROM SCHOOL! (Well, almost)

In 1917, while a senior at Oak Park High School, Hemingway got into a bit of trouble. He and some buddies got together and published an underground magazine called “Jazz Journal.” In the 1910s, “jazz” was by itself a suggestive word, carrying modern, even scandalous connotations (nightlife, sexual looseness).

By Craig Mindrum

In 1917, while a senior at Oak Park High School, Hemingway got into some trouble. He and some buddies got together and published an underground magazine called “Jazz Journal.” In the 1910s, “jazz” was by itself a suggestive word, carrying modern, even scandalous connotations (nightlife, sexual looseness).

One of the magazine co-conspirators, Ray Ohlsen, described the incident:

“We had a paper called the ‘Jazz Journal.’ There was only one copy—about five of us edited it. What we did was put in a lot of dirty jokes and attributed them to some of our teachers. It just happened that while I was practicing for the class play somebody stole the copy I had in my English book. Ernie called me up that night and wanted to know where it was. I told him I had it. He said I'd better look and check and sure enough I couldn't find it. Well, the principal Mr. McDaniel had it and we were in on the carpet.”

Threat of expulsion

The magazine raised enough concern from school authorities and from parents that there was talk of suspension or expulsion. Hemingway and the others involved were summoned to the principal’s office. The magazine was brought out as proof of indecency. There was pressure to punish the boys harshly.

Saved by the play

Hemingway was saved, however, because of an otherwise unrelated fact: He had tried out for the Senior play (“Beau Brimmel”) and got a role. (This had been a dream of his since the time he started school.)

The play was to open the week right after the boys got into trouble. Fortunately for them all, a school teacher and director of the play, Fannie Biggs, interceded for the boys and prevented them from more drastic action.

Hemingway’s buddy Ohlsen continues the story: “We would have all gotten expelled if it weren't for our English teacher Miss Biggs who we thought must have lied and told the principal that we had come to her for advice and that we had promised her we would discontinue the magazine. If it wasn't for her we would have been expelled.”

Ongoing repercussions

Hemingway narrowly avoided trouble, and the play went on as scheduled but repercussions continued in the Hemingway family. Ernest resented the lack of support shown by his parents about the incident. He had a grudge; he felt betrayed by his parents (especially his mother). To him, other boys had more support from their parents than he. For example, one of his classmates got in trouble and his father came to school standing up for him stoutly and saying the school was being too severe. Hemingway blurted out in a group, “Neither of my parents would come to school for me no matter how right I was. I just have to take it.”

Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker treats Hemingway’s high-school skirmishes as early indicators of his lifelong pattern of testing authority and experiencing family conflict over his behavior and writing.

Other biographies agree that this was not mere adolescent mischief. It was a symbolic first instance of literary boundary-testing.

Source: Buske, Morris R. Hemingway's Education, a Re-Examination: Oak Park High School and the Legacy of Principal Hanna, 2007. Reference Book Collection. Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park Archives, Oak Park Public Library Special Collections, Oak Park, IL.

So I ignored him and wrote two sentences:Hemingway’s advice for lawyers and other writers in A Moveable Feast

He was sitting at the next table, a tall fat young man with spectacles. He had ordered a beer. I thought I would ignore him and see if I could write. So I ignored him and wrote two sentences.

By Brian C. Potts*

He was sitting at the next table, a tall fat young man with spectacles. He had ordered a beer. I thought I would ignore him and see if I could write. So I ignored him and wrote two sentences.[1]

It won’t surprise you that Hemingway was sometimes solitary, sometimes gregarious; sometimes warm and sometimes gruff. Who isn’t?

And if you’re a writer, it won’t surprise you that Hemingway—one of the greatest writers ever—often worried about money, especially early in his career.

But would it surprise you that Hemingway—winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature—faced writer’s block?

Would it surprise you that Hemingway rewrote his works over and over and over?

That Hemingway was an early bird?

Hemingway was a model of the hardworking artist not dependent on uncertain muses but on simply sitting down to write. Indeed, I have found that A Moveable Feast—Hemingway’s pseudo-memoir of his Paris years—overflows with blunt advice for lawyers, legal writers, and writers in general.

Reading Hemingway can make you a better writer and a better lawyer. In One True Sentence: Hemingway’s Advice for Lawyers in A Moveable Feast, 25 Journal of Appellate Practice and Process 391 (2025), I glean 35 nuggets of wisdom for lawyers and other writers. Here are some appetizers:

2. Flow

The story was writing itself and I was having a hard time keeping up with it.[2]

When you are flowing, keep going. Maintain the flow and finish while you have momentum. If you stop, you waste time figuring out where you were and where you were going.[3]

3. Rewrite

That fall of 1925 he was upset because I would not show him the manuscript of the first draft of The Sun Also Rises. I explained to him that it would mean nothing until I had gone over it and rewritten it and that I did not want to discuss it or show it to anyone first.[4]

When you finish the first draft and a round of editing, set your work aside and return to it refreshed. Embrace the process of rewriting, editing, and proofreading. There is no great writing. Only great rewriting.[5]

14. Plain language

If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.[6]

Avoid long wind-ups, legalese, and ornamentation. Use plain language. Write tidysentences. Write simply. And beautifully. And sometimes passionately.

Be honest and clear.[7]

20. War stories

You could always mention a general, though, that the general you were talking to had beaten. The general you were talking to would praise the beaten general greatly and go happily into detail on how he had beaten him.[8]

Cherish your war stories. Some will come earlier in your career than you expect. Keep track of them. When you close a case or a deal or an estate, take the time to write a note to yourself about it. Hemingway was a consummate journaler; in fact, A Moveable Feast is rooted in his journals. In your own journaling, ask yourself: What was the problem? Where was the drama and intrigue? How did the knot unravel?[9]

24. Walk

I would walk along the quais when I had finished work or when I was trying to think something out. It was easier to think if I was walking and doing something or seeing people doing something that they understood.[10]

Take breaks and good walks to sort through ideas and discover new ones. Many great writers swear by this.[11]

31. Stories

I told Joyce of my first meeting with him in Ezra’s studio with the girls in the long fur coats and it made him happy to hear the story.[12]

“Write the best story that you can and write it as straight as you can.”[13]

Tell clear and compelling stories. They make people happy. So they make people listen.[14]

I tell my law students to rejoice that there is no such thing as great writing; only great rewriting. So don’t worry that your first draft is garbage. Of course it is. But you will work hard and your rewriting will be gold. The sooner you start writing, the sooner you can start rewriting. Start with one true sentence. Then ignore distractions and write two more.

* For Maria, Mark, and Servant of God Father Patrick Ryan. My thanks to Professor Tessa L. Dysart of the University of Arizona, Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process; to Dr. Craig Mindrum of The Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park; and to my Research Assistants Bar Sadeh and Mixa Hernandez.

[1] Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast 92 (Mary Hemingway, ed., 1964).

[2] Id. at 6.

[3] Brian C. Potts, One True Sentence: Hemingway’s Advice for Lawyers in A Moveable Feast, 25 J. App. Prac. and Process 391, 394 (2025).

[4] Hemingway, supra note 1, at 184.

[5] Potts, supra note 3, at 395.

[6] Hemingway, supra note 1, at 12.

[7] Potts, supra note 3, at 402.

[8] Hemingway, supra note 1, at 28.

[9] Potts, supra note 3, at 406.

[10] Hemingway, supra note 1, at 43.

[11] Potts, supra note 3, at 409.

[12] Hemingway, supra note 1, at 129.

[13] Id. at 183.

[14] Potts, supra note 3, at 415.

Considering Cather and Hemingway: An Unlikely Pairing?

Speaking of Willa Cather, can anyone of our readers place this Hemingway quote? (Noting his bumping iambs, his simple declarative clauses, his monosyllabic repetitions, and the Bachian musicality in “made me bite my tongue,” “When the straw settled down,” or “from under the buffalo hide.”)

By Michael Seefeldt

Speaking of Willa Cather, can anyone of our readers place this Hemingway quote? (Noting his bumping iambs, his simple declarative clauses, his monosyllabic repetitions, and the Bachian musicality in “made me bite my tongue,” “When the straw settled down,” or “from under the buffalo hide.”)

“I tried to go to sleep, but the jolting made me bite my tongue, and I soon began to ache all over. When the straw settled down, I had a hard bed. Cautiously I slipped from under the buffalo hide, got up on my knees and peered over the side of the wagon. There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.”

Change the “peered’ to “looked” and remove the “Cautiously” (and a couple of commas) and it is vintage Hemingway. Of course those things are there and it is not, but it is very close, and some of you may have recognized Jim Burton’s wonderment in an opening scene from Willa Cather’s My Antonia.

“Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

“Artistic growth is, more than it is anything else, a refining of the sense of truthfulness. The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist, knows how difficult it is.”

The first quote is Hemingway writing in his fifties (A Moveable Feast), recalling his early Paris efforts. The second is Cather, in her forties, from The Song of the Lark. More:

“Art, it seems to me, should simplify. That, indeed, is very nearly the whole of the higher artistic process; finding what conventions of form and what detail one can do without and yet preserve the spirit of the whole.”

“If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.”

“The condition every art requires is, not so much freedom from restriction, as freedom from adulteration and from the intrusion of foreign matter.”

The first and third this time are Cather, from “On the Art of Fiction” in the periodical Borzoi in 1920, and “Four Letters: Escapism” in Commonweal, 1936. The second is a continuation of the previous from A Moveable Feast. Certainly both wrote in a simplified style, eschewing prolix verbiage.

Both also had a close feel for the land, often in reminiscent mode. They wrote rich, but non florid, descriptions of nature, often using nature to create both a spiritual atmosphere and a realistic setting for characters and events. H. R. Stoneback, standing in for Ernest, who tended to be mute on topics closest to his depths, linked the two in his essay “Pilgrimage Variations: Hemingway’s Sacred Landscapes” (R&L, 2003, Vol 35.2-3). More prone to address such things openly, Cather used earth metaphors in a similar, if broader vein: “Religion and art spring from the same root and are close kin.”

They also shared concrete features: both were expatriates of sorts from the middle west, she to the eastern establishment, he to Europe and Cuba; but both drew heavily on a pastoral childhood there. Both started out in journalism, and had significant tenures, she as editor for McClure’s for many years, he as a foreign correspondent in Paris for a couple of salad years, but in various riffs thereafter. Both knew they had to cut themselves from journalism for the sake of their art, but both took with them pristine habits which helped significantly to form that art.

Both wrote great (WW I) war novels, A Farewell to Arms, possibly Hemingway’s most read book, and One of Ours, which won Cather the Pulitzer. Both had subordinated themselves when young before dominating, possibly lesbian literary women: Hemingway with Gertrude Stein (and Alice Toklas); Cather with Annie Fields, widow of James Fields of publisher giants Ticknor and Fields. (Her partner was Sarah Orne Jewett in possibly a “Boston marriage,” i.e., Victorian/Edwardian women living/ loving together, but not physical). And both conveyed in much of their work a languid sense of lost time, futility, even despair; while centering it all on a tested-firm moral core, whether in Antonia’s spit, Alexandra’s powerful solitude in O Pioneers!, or Henry Jordan’s universal Spanish mission. Or Santiago’s perseverance in The Old Man and the Sea, or the grandmother in “Old Mrs. Harris,” Cather’s most famous short story. The list is long and consistent and almost always includes the uncertain mix of success and fatal failure: Cantwell in Across the River, the protagonist of The Professor’s House, the Archbishop to whom death comes.

For a brief spell the fatalistic even creeps directly into their titles — Death Comes to the Archbishop, “A Natural History of the Dead,” and Death in the Afternoon all appearing in a five year window framing the start of the Great Depression (1927-32). And death, solitude, disappointment, or tragedy in love mark central themes throughout the work of both.

Of course they were different, he big and brawling and irreverent, hiding his sentiment; she proper and staid and respectful to the point of morally rejecting Oscar Wilde. He cut a dashing figure, a near Adonis in young manhood; a comely picture of her cannot be found.

Each lost painfully in early love: he with nurse Agnes in Milan; she supposedly with an athletic coed, Louise Pound, at the University of Nebraska. He totaled four wives on three continents, she was with her companion, Edith Lewis, for forty years in New York City. Her works are more quiet, and, being a generation earlier, not born in post World War I disaffection. Her plot line is more slow developing, and often cuts across time separations of a decade or more (Pioneers, Lost Lady, Antonia, Archbishop); his often take but a very few days (To Have and Have Not, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Across the River the River and Into the Trees, The Old Man and the Sea).

But in the end their deeper similarities should not escape us: each, though differently oriented, knew the darker side. “There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields.” “Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee.” Her “There . . . nothing . . . no . . . no . . .no . . . there . . . not . . . there . . . nothing . . . not” ends in the future of the land. His blacker “Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada” does not.

But if you were to try to pick the male and female American novelists of that first half of the twentieth century, you would be hard pressed to improve on their unlikely pairing. Richard Edel, the great Henry James scholar (Hadley’s favorite novelist), was surely a bit in his cups when he said, “The time will come when she’ll be ranked above Hemingway.” But it points us to a fuller awareness of her significance.

(Willa Sibert Cather, 1873-1947; Ernest Miller Hemingway, 1899-1961)

Michael Seefeldt served on the board of the Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park from 1991-2003 in various capacities and was a Professor of Medicine at UIC College of Medicine

This article was first published in the Hemingway Foundation Dispatch Spring 2006

Teaching Hemingway and Faulkner in Unison

As the Director of the English Honors Program here at Western Kentucky University, I developed a course entitled “Honors Hemingway and Faulkner,” and I have taught this class each fall for over a decade.

by Professor Walker Rutledge

Editor’s note: We received a letter upon request from Professor Walker Rutledge of Western Kentucky University, who visits the Hemingway Museum and Birthplace Home yearly with his English honors class. In the letter he explains his teaching methodology in pairing Hemingway and Faulkner. We hope to get more news from Professor Rutledge after his presentation at the International Hemingway Conference in Spain. Teaching Hemingway and Faulkner in Unison

As the Director of the English Honors Program here at Western Kentucky University, I developed a course entitled “Honors Hemingway and Faulkner,” and I have taught this class each fall for over a decade. Having discovered long ago that literature most fully comes to life for students when they can actually establish an identity with the author’s time, place, and culture, I wanted to build into the course two field trips—one to Hemingway’s home in Oak Park, Illinois, and one to the Faulkner sites in Oxford, Mississippi. Thanks to the University’s commitment to student engagement and to the generosity of the University Honors Program, we have been able to schedule a Hemingway Weekend and a Faulkner Weekend each year. As weathered as the expression may be, the effect of these fieldtrips upon the students can only be called “immeasurable.” The material comes to breathe in a way it never would otherwise.

As for my particular instructional approach of pairing Hemingway with Faulkner, this is a pedagogical technique that I first began using in American literature classes. With so much of the cultural and intellectual history encapsulated by duos—think Jefferson and Hamilton, or Grant and Lee—I thought that the same approach might work well with literary figures. Indeed it did! My first pairings were Jonathan Edwards and Benjamin Franklin, then Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

But nowhere has this approach been more successful than with America’s two most famous Nobel Laureates—Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner. By studying Faulkner, one can more fully appreciate what Hemingway is doing; by studying Hemingway, one can more fully appreciate what Faulkner is doing. The two play off each other like no one else.

Recently I have been gratified to learn that others have shown an interest in this approach. At the 12th Biennial International Hemingway Conference this summer, I have been invited to deliver a paper entitled “Hemingway and Faulkner: Using One to Teach the Other.” I shall certainly be recording my impressions at Malaga and Ronda.

Walker Rutledge, Assistant Professor

Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, Kentucky

This article was originally published in Hemingway Foundations Dispatch Spring 2006

Farming in Hemingway’s Family

It was a pleasant Wendy's. I ordered a cup of coffee and took it out front to a cement table, just feet from gridlocked Harlem Avenue. Next door, cars rolled in and out of a Shell station at the corner of Higgins Road in northeast Illinois. To the West, stacks of empty balconies fronted a series of tall, brick apartment buildings. Thunderous Kennedy expressway traffic roared past in a gulch 200 feet to the north. I had arrived at the farm of Ernest Hemingway’s great-grandfather.

By Eric Kammerer

“It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait." Ernest Hemingway - A Moveable Feast

It was a pleasant Wendy's. I ordered a cup of coffee and took it out front to a cement table, just feet from gridlocked Harlem Avenue. Next door, cars rolled in and out of a Shell station at the corner of Higgins Road in northeast Illinois. To the West, stacks of empty balconies fronted a series of tall, brick apartment buildings. Thunderous Kennedy expressway traffic roared past in a gulch 200 feet to the north. I had arrived at the farm of Ernest Hemingway’s great-grandfather.

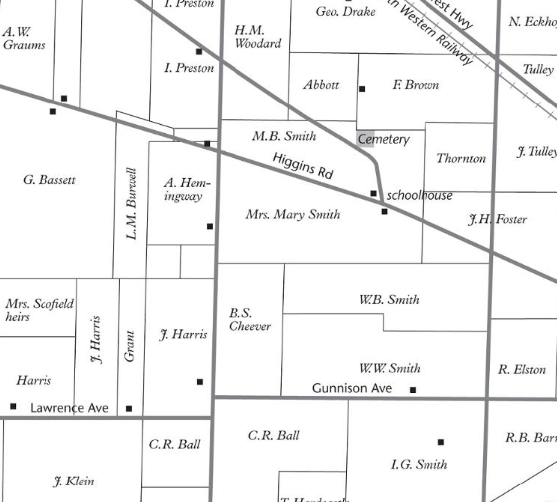

Allen Hemingway (1808-1886) was Ernest Hemingway's paternal great-grandfather. He arrived in Illinois in 1854,[1] settling on 80 acres in the outlying rural community of Leyden,[2] northwest of Chicago. His farm was in what is now Chicago's Oriole Park neighborhood, part of the Norwood Park community area. He came from Terryville, Connecticut, where he served as postmaster[3] and owned a general store.[4]

More than 70 years later, Allen's youngest son, Anson, claimed the move was motivated by his father's failing health.[5] If so, his dad chose a strenuous new lifestyle, as a combination farmer and commuting merchant, with a side gig as a Sunday school teacher.

A new railroad

The Illinois and Wisconsin Railroad was completed through Leyden in 1853. This new transportation option allowed Allen, undoubtedly after leaving a long chore list for his three sons, to travel into Chicago to operate his wholesale clock store, located on Clark Street below the offices of the fledgling Chicago Tribune.[6] The Seth Thomas Clock Company was incorporated in 1853 near where the Hemingways had lived in Connecticut, so Allen likely had connections in the timepiece business.

Leaving a legacy

But the move may also have been prompted by a desire to leave a legacy of land. As his second wife wrote: "Mr. Hemingway is quite engaged about going out West to buy a farm for his boys. . ."[7] This dream would be dashed by the Civil War, when disease killed his two oldest sons, Union Army soldiers. Anson, Ernest Hemingway's grandfather, would go on to a long life after his Civil War service, working for the YMCA and then in real estate.

Ernest and farming

Ernest Hemingway was no stranger to farms. His parents put him to work on their forty-acre patch, which they dubbed Longmont, after a farm in their favorite Victorian novel. Longmont was across the lake from Windemere, the Hemingway’s summer home in Michigan. The family began spending summers there around 1899, the year Ernest was born. They returned nearly every summer during his childhood and teenage years, well into the 1910s.

Ernest developed an aversion to digging potatoes and picking fruit. The situation sowed seeds of adolescent rebellion, which would cause bitter conflicts with his parents.[8] Ernest shared the attitude of his maternal grandfather, Ernest Hall, toward farm work. Marcelline Hemingway reported that Hall said he "hated" it.[9]

Moving between two worlds

Allen Hemingway moved daily between two eras: building a tranquil country home for his boys while riding the train downtown to work in "a rough, vulgar town that seemed to wallow in its own love of money and increasing commercialism."[10]

Chicago’s population exploded 300% between 1850 and 1860 to 112,000. The city grew due to an increasing role as a rail hub, and the Illinois and Michigan Canal opening a route to the Mississippi.[11]

Ernest Hemingway, who emerged from a proper Victorian household to post-war disillusionment, also moved between eras personally and artistically. Back in Chicago at age 20, he "wanted to be seen in exile from the banal Midwest and unencumbered by family, business, and money concerns."[12]

From farms to car washes

At the corner of Harlem Avenue and Higgins Road, the land that used to be Allen Hemingway's farm now features gasoline, car washes, and Baconators™. The convenience store in the gas station sells everyday necessities, just like Allen Hemingway's store in Connecticut.

While you're in the area, consider visiting the Norwood Park Historical Society, where exhibits show an evolution from pioneer farming settlement, to independent 19th-century railroad suburb, to city neighborhood. You can also visit Allen Hemingway's gravesite in Union Ridge Cemetery. You can get a great cup of coffee at October Cafe.

Hemingway’s birthplace home

Four short miles away, you can enter the Victorian era by touring Ernest Hemingway's birthplace home (https://www.hemingwaybirthplace.com/) in Oak Park, Illinois.

Eric Kammerer is a volunteer docent at the Ernest Hemingway Birthplace Museum. He is a writer from the western suburbs of Chicago.

[1] Hemingway, P. S. (1988). The Hemingways: Past & present and allied families. Gateway Press.

[2] Conzen, Michael P. and Keating, Ann Durkin. (2005). Land Subdivision and Urbanization on Chicago’s Northwest Side. Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved at http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1754.html

[3] Litchfield County Postmasters, retrieved at https://www.cga.ct.gov/hco/img/history/norton/LitchfieldPostmasters.pdf

[4] Taylor, William Harrison. (1890) Taylor’s Souvenir of the Capitol.

[5] Anson T. Hemingway, Early Settler Celebrates his Eighty-Second Birthday Anniversary -- Recalls Memories of Days That Are Gone. (1926, August 28). Oak Leaves.

[6] Hemingway, P.S.

[7] Nagel, James. (1996). Ernest Hemingway: The Oak Park Legacy. University of Alabama Press.

[8] Dearborn, Mary V. (2017). Ernest Hemingway: A Biography. Vintage Books.

[9] Sanford, Marcelline Sanford. (1962) At the Hemingways. University of Idaho Press.

[10] Moore, Michelle E. (2019). Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Bloomsbury Academic

[11] Bross, W. (1876). History of Chicago: historical and commercial statistics, sketches, facts and figures, republished from the "Daily Democratic press" ; What I remember of early Chicago, a lecture, delivered in McCormick's hall, January 23, 1876 (Tribune, January 24th). Chicago: Jansen, McClurg & Co..

[12] Ibid.

*1861 Development Map of Norwood Park Area, courtesy of the Newberry Library

**photo credit, exhibit at the Norwood Park Historical Society

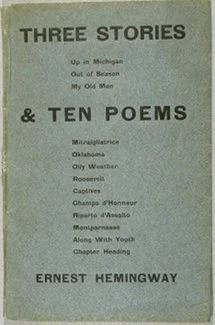

Hemingway shows his promise as a writer: Three Stories and Ten Poems

To wrap up our discussion of his earliest writing, I’m going to take a look at Three Stories and Ten Poems, his official first book (1923). I’ll focus on two of the three stories in the book, then discuss some of his poems.

By Craig Mindrum, Ph.D.

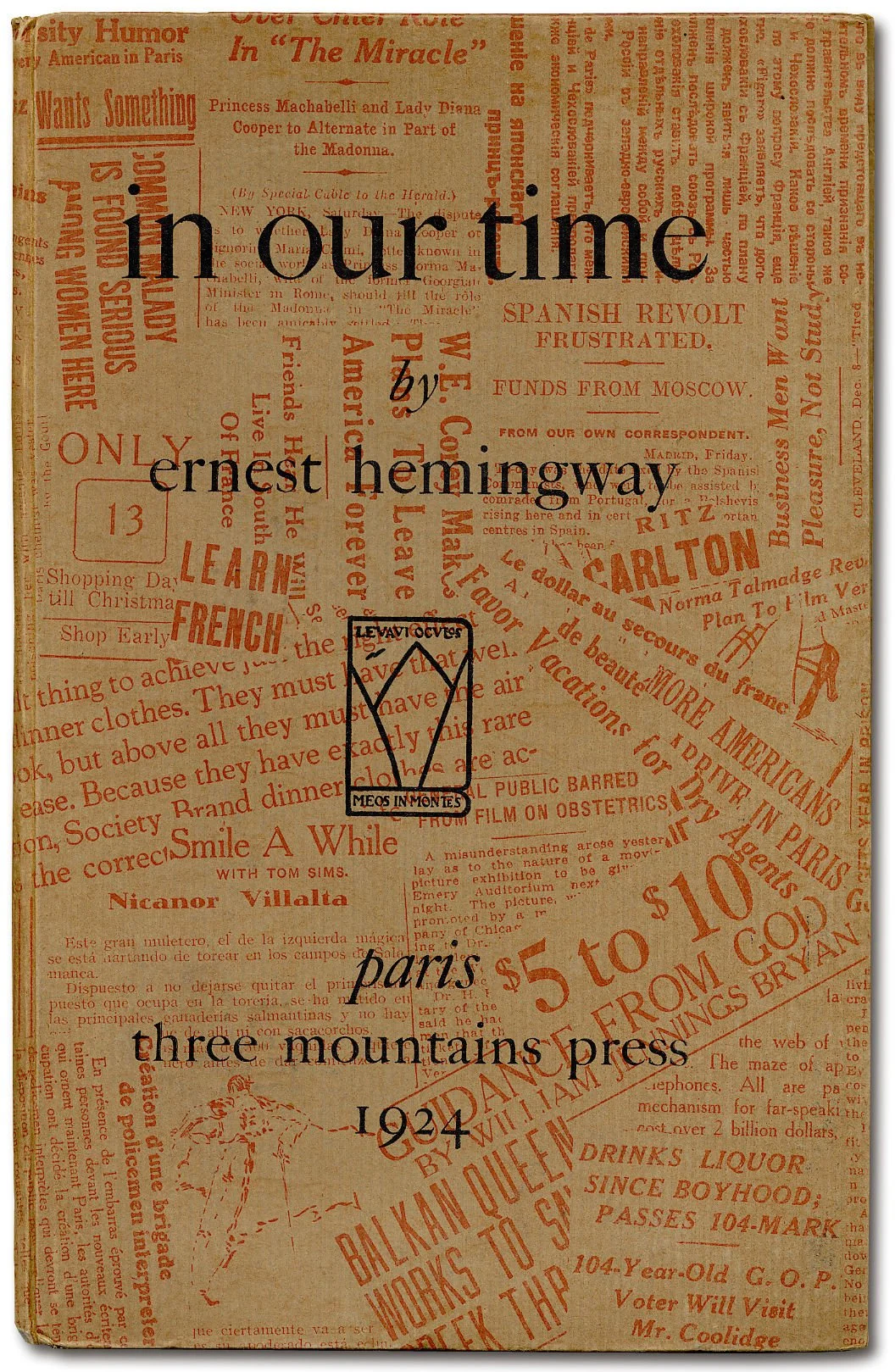

In previous blogs, we have focused on Hemingway’s early years as a writer. In two blogs[1], we discussed in our time, a series of powerful vignettes about war and the threat of death, published in 1923. We then looked at [2] his 1924 edition of In Our Time, where the vignettes are used as interchapters between some excellent early stories.

To wrap up our discussion of his earliest writing, I’m going to take a look at Three Stories and Ten Poems, his official first book (1923). I’ll focus on two of the three stories in the book, then discuss some of his poems.

“Up in Michigan”

In Hemingway’s early story “Up in Michigan,” the quiet longing of a young woman turns abruptly into a harrowing scene of sexual violence. Liz Coates, a waitress in the small town of Hortons Bay, Michigan, develops a romantic infatuation with Jim Gilmore, a local blacksmith. One evening, after a dinner with friends and too much to drink, Jim takes Liz for a walk and then assaults her on a cold dock, ignoring her resistance. The scene is brief but brutal, rendered in Hemingway’s early minimalist style, which makes the violence feel all the more stark.

Jim puts his hand on Liz’s leg and starts to move up. “Don’t, Jim,” she says. “You mustn’t Jim, you mustn’t.” He pays no attention to her.

The boards were hard. Jim had her dress up and was trying to do something to her. She was frightened but she wanted it. She had to have it but it frightened her.

“You mustn't do it Jim. You mustn't.”

“I got to. I'm going to. You know we got to.”

“No we haven't Jim. We ain't got to. Oh it isn't right. Oh it's so big and it hurts so. You can't. Oh Jim. Jim. Oh.”

When Three Stories and Ten Poems was first published in 1923, the story received little attention, largely because it was printed in a small edition by a Paris avant-garde press. But when Hemingway tried to reintroduce the story to American readers, publishers objected. His editor at Scribner’s, Maxwell Perkins, refused to include it in collections for years. A century later, readers approach the same scene with more clarity about consent and trauma.

What once passed as a story of “rough passion” is now unmistakably identified as rape. The unknown narrator of Hemingway’s story is silent about Liz’s suffering, which raises uncomfortable questions. The story remains powerful, but today it demands to be read not only as literature, but as a reflection of gendered violence—and the cultural blind spots that long protected it.

One can feel justified anger at how Hemingway handles the aftermath of the rape, where he undermines the trauma of the event. Liz has trouble extricating herself from under Jim, who has passed out. She wiggles free, then ends up placing her coat over him to keep him warm. She tucks the coat around him. She kisses his cheek.

“Out of Season”

“Out of Season” is an oblique and difficult story. Even here, early in his career, Hemingway leaves much unsaid, forcing the reader to fill in the blanks. It appears to be, in the end, a story of marital discontent and malaise. Nothing goes right (one meaning of the title—recall Hamlet: (“The season is out of joint”).

The story is set in Italy and follows an American couple—referred to only as the young gentleman (sometimes just “y.g.”) and his wife—as they set out on a fishing trip on a cold day led by a local, Peduzzi, a drunken and slightly pathetic guide. The couple and Peduzzi walk through the town and out into the countryside toward the stream where they plan to fish, but the trip is disorganized and strange from the start. Peduzzi doesn’t have a fishing permit (a real source of concern for the young couple), doesn’t know where to get bait, and doesn’t have the right equipment.

The wife becomes increasingly irritated and eventually turns back, leaving the young man and Peduzzi to continue. When they finally reach the stream, they find it too high and fast to fish. The story ends with a moment of vague despair. Peduzzi wants to fish again in the morning, but the young gentleman (who has bankrolled Peduzzi’s drinking throughout the day) indicates he will not be joining them the next day. Attending to his marriage may be his motive.

The couple’s attempt at a leisure activity—fishing—may be a sign of trying to bridge the gap between them, but it fails miserably. The American couple and the Italian guide can’t communicate well, and the result is a series of small failures and embarrassments. The awkwardness of cross-cultural interaction is used to explore the couple’s own inability to communicate.

The season is wrong for fishing, the cold day mirrors the marriage, and the human connections are out of sync. Like much of Hemingway’s work, the story refuses easy resolution.

The Poems

The ten poems in Three Stories and Ten Poems range from shallow exercises to a few surprisingly mature pieces that hint at Hemingway’s emerging voice. The standout is “Champs d’Honneur” (“Fields of Honor”), a biting indictment of anonymous war that distills Hemingway’s postwar cynicism:

Soldiers never do die well;

Crosses mark the places—

Wooden crosses where they fell,

Stuck above their faces.

Soldiers pitch and cough and twitch—

all the world roars red and black;

Soldiers smother in a ditch,

Choking through the whole attack.

I admire the rhymes here—a kind of rhetorical order undermined by the disorder and horror described in the poem. It also includes effective alliteration and off-rhyming: “pitch and cough and twitch.”

“Riparto d’Assalto” (“Assault Unit”) includes what I would term immature and tentative use of repetition and rhyme. But it has its merits. The poem is more subdued than “Champs d’Honneur,” but just as affecting—a terse portrait of soldiers as pawns, advancing toward death with no names and no heroics, only cold inevitability.

In “Montparnasse” (a neighborhood in Paris famous for being a hub of artists, poets, and expatriates in the 1920s) Hemingway turns his attention to the bohemian world of Paris, capturing the psychological detachment of expatriates and artists who circle around death and disillusionment with a practiced cool.

These poems are not perfect, but they reveal a young writer already rejecting sentimentality and testing the emotional compression that would become his hallmark. The rest of the poems—ranging from crass (“Oklahoma”) to aimless or overwritten (“Ultimately,” “The Soul of Spain”)—serve mostly to remind us that Hemingway’s use of spare, precise language was hard-won.

In Our Time: Searching for Order Amid Chaos

Ernest Hemingway published In Our Time in 1925, a year when people still were reeling from the impact of World War I. Hemingway and others had believed World War I was going to be the war to end all wars but quickly learned it was a futile blood bath. There were no heroes—just passive victims hit by shells in trenches, poisoned with gas, or scorched by flame-throwers.

By Nancy W. Sindelar, Ph.D.

Ernest Hemingway published In Our Time in 1925, a year when people still were reeling from the impact of World War I. Hemingway and others had believed World War I was going to be the war to end all wars but quickly learned it was a futile blood bath. There were no heroes—just passive victims hit by shells in trenches, poisoned with gas, or scorched by flame-throwers. The horrors of the war left the world filled with people who felt betrayed by their leaders, their culture, and their institutions. The war brought a basic disillusionment and the realization that the old concepts and values embedded in Christianity and other ethical systems of the western world had not served to save mankind from the catastrophes inherent in the war.

An experimental structure

This disillusionment is present throughout Hemingway’s In Our Time, a series of short stories interspersed with interchapter commentary (vignettes that had been published by themselves the previous year, 1924). The short stories are organized in largely chronological order and tell a single larger story about life circa 1925. Most are about Nick Adams, whose experiences closely reflect those of a young Hemingway. The short stories tell the tale of daily life but are juxtaposed against the interchapters which focus on the world of war, politics and the chaos of the outside world. The structure of the book was experimental. Hemingway said it was “Like looking with your eyes at something, say a passing coastline, and then looking at it with 15x binoculars—Or rather, maybe looking at it and then going in and living in it and then coming out and looking at it again.” [1]

Early influences

Hemingway’s personal experiences influenced the content. Born in 1899 and raised in Victorian era Oak Park, Illinois, Christian religious principles, a traditional education in public schools and a strong work ethic were imparted to Ernest as a child. His father, Dr. Clarence Hemingway, was a disciplined medical doctor and a devout member of the Congregationalist church. Ernest’s mother, Grace Hall Hemingway, liked to think of herself as an English gentlewoman. Her parents emigrated from England and eventually built the Queen Anne house with a turret and six bedrooms in Oak Park, where Ernest was born and spent the first six years of his life. During summers, the family left their comfortable life in Oak Park and went to their rustic cottage in northern Michigan, where Ernest’s father taught his son to hunt and fish.

Hemingway joins the war

Both of Hemingway’s grandfathers lived in Oak Park and were veterans of the Civil War. His paternal grandfather, Anson Hemingway, inspired Ernest’s belief that war was the venue for men to display courage and honor. As Ernest grew up, he observed Grandfather Anson proudly wearing his Civil War uniform, displaying his medals, and marching with his comrades in the yearly Oak Park Memorial Day parades. When the United States entered World War I in April,1917, Ernest couldn’t wait to get involved. Though he couldn’t enlist due to poor eyesight, he eventually went to Italy as a Red Cross ambulance driver, fully embracing the values and teachings of his grandfathers.

A different morality

The first eighteen years of Ernest’s life were idyllic. He had the love and attention of his parents and grandparents, yet he hungered to understand the challenges and actions needed to live in an ever-changing world. As time passed, he developed an autonomous morality, in which his personal standards were different from those of his parents. After graduation from high school, Ernest moved to Kansas City and got a job as a cub reporter for The Kansas City Star, but when the Red Cross came through town, he jumped at the chance to go to Italy and experience the war. He told his sister, “I can’t let a show like this go on without getting in on it.”[2]

Hemingway’s wartime injuries

Hemingway went to Italy looking for adventure and got more than he had bargained for. He soon learned war was a sordid bloodbath where one was required to carry parts of dead bodies, and risking sustained injuries that would last a lifetime. Ernest was hoping to display the honor and courage his grandfathers had talked about but was a passive victim, blown up in a trench while taking cigarettes and chocolate to Italian soldiers. When he arrived at the American Red Cross hospital in Milan, he had a machine gun slug in his right foot, another behind his right kneecap, hundreds of steel fragments lodged in his legs, and was swathed in bandages. He had learned that modern warfare was different from what Grandfather Anson had experienced. His worldview had changed, and he now understood that surviving in this world required new actions—actions that trumped some of the religious teachings of his parents and some of the manners and morals he had learned in Oak Park.

A rejection of pre-war values

After the war, Ernest returned to Oak Park then moved to Chicago, where he met Hadley Richardson. She supported Ernest’s dream of becoming a writer, and after their marriage, the couple moved to Paris and embraced all Paris had to offer. Paris in the 1920s was a mecca for artists and writers. Given the bloodshed of World War I, prewar values were rejected and there was much experimentation with new lifestyles, collaborations, and relationships. Expat artists and writers experienced greater acceptance in the European environment than in the prohibition-era United States, and new forms of art and literature thrived.

In Our Time is the work of a young Hemingway at the outset of his career; it is a pivotal piece in Ernest’s commitment to a new method of writing and a new set of values. Ernest tried to write clearly and honestly about life in the modern world. Writing to his father from Paris, he said, “You see I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of actual life—not to just depict life—or criticize it—but to actually make it alive. So that when you have read something by me you actually experience the thing. You can’t do this without putting the bad and the ugly as well as what is beautiful.”[3]

His letter to his father about the ugly as well as the beautiful was, no doubt, to prepare his parents for the transition to a new set of values. In Our Time documents questions that now concerned the author. What is bravery? What is fear? What constitutes a good relationship between a man and a woman? Answers to these questions were based on his experiences and described with honesty and images that were sometimes blunt, sexual, or bloody.

The format of In Our Time is an experimental combination of interchapters and short stories. The interchapters provide flashes of death, violence, and chaos in the outside world while the short stories focus on Hemingway’s personal experiences and document his efforts to bring order to his personal life by writing about it. They reveal his up-close-and-personal encounters with death, violence, and chaos.

Disillusionment with war

The book begins with the sentence, “Everybody was drunk” and reveals Ernest’s disillusionment with war. [4] There are no heroes, just drunk soldiers marching in a chaotic retreat. Though Ernest only read about it, the first interchapter is his reflection on the World War I Battle of Caporetto. The Austrians had broken through the Italian lines, and the Italians were retreating. Houses were evacuated, and women and children were loaded in trucks. Ernest first mentions the horror, confusion, and irrationality of modern warfare in In Our Time, but eventually will more fully describe the retreat in A Farewell to Arms.

His experience with Mussolini

Ernest’s negative depictions of the Italian army and his lifelong dislike of fascism were influenced by his personal contempt toward Benito Mussolini. He had interviewed him in 1923, shortly after he seized power, and in an article for the Toronto Star called him "the biggest bluff in Europe.”[5] Ernest had observed Mussolini trying to impress the media by pretending to be deeply absorbed in reading, while, in reality, he was holding a French–English dictionary upside down.

Near-death experiences

The interchapter prior to the Chapter 7 short story, “Soldier’s Home,” focuses on a soldier who had been blown up in a trench. The description mirrors Ernest’s own near-death experience in Italy as well as his growing ambivalence regarding prewar attitudes toward religion and sexuality. Fearing he will die, the soldier prays “Dear Jesus get me out…please keep me from getting killed…I’ll tell everyone in the world you are the only one that matters.”[6] However, the interchapter ends without transformation: “…he did not tell the girl he went upstairs with at the Villa Rosa about Jesus. And he never told anyone.”[7]

Alienation

The interchapter is followed by “A Soldier’s Home,” a short story that focuses a soldier returning home after World War I. The story begins with the background of the soldier’s life before the war. He attended a Methodist college and was a member of a fraternity. The photo of his fraternity brothers, all of whom were wearing exactly the same thing, represents the conformist mentality of prewar, Midwestern America. When the soldier returns from the war, he, along with Ernest, is troubled by the re-entry into his old life. He is changed by the war and feels alienated from everyone in his hometown, including his parents. He spends much of his time reading about the war but wishes there were more maps because he wants to pinpoint his experiences. Metaphorically, the soldier, like Ernest, is trying to understand and bring order to his war experiences. When the mother chides the soldier for not working by saying God cannot have any idle hands in his Kingdom, he replies that he is not in His Kingdom. Though he feels embarrassed for saying this, he no longer can pray with her.

Relevant to today

The interchapters and the short stories in In Our Time explore themes of death, separation, and alienation attached to World War I or periphery events. However, In Our Time is as relevant today as it was in 1925. Hemingway experienced the horrors of World War I firsthand and filtered his experiences by writing both the interchapters and the short stories. Today, all we need to do is flip on our TVs to see the destruction in Gaza, the bombed-out towns in Ukraine, or experience the political divide at home. Like Ernest, we are confronted with the bloodshed of modern warfare and question the values and integrity of our political leaders. Like Ernest we view the chaos of the world around us and then retreat to our private lives, hoping to find order and understanding. We long for peace, economic security, and political stability but are routinely barraged with scenes of bombed-out towns, starving children, and stories of political corruption. As we look through our 15x binoculars at our personal lives, we sense, like Hemingway, the intoxicated chaos of the outside world.

The themes of In Our Time are one hundred years old, but they resonate across time and unite readers through the shared human experience of dealing with violence, separation, and change. They are timeless because they reveal the universal aspects of the human condition and remind us that good literature has the power to bridge differences and connect us through the fundamental emotions we all share.

[1] Ernest Hemingway, Letter to Edmund Wilson, October18,1924 in Selected Letters 1917-1961, New York: Scriber’s Sons, 1981, Carlos Baker, ed.,128.

[2] Ernest Hemingway to Marcelline Hemingway, quoted in Sanford, At the Hemingways, Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1999, 156-7.

[3] Ernest Hemingway, Letter to Clarence Hemingway, March 20,1925 in Selected Letters1917-1961, New York: Scriber’s Sons, 1981, Carlos Baker, ed.,153.

[4] Ernest Hemingway, In Our Time, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925

[5] Ernest Hemingway, “Mussolini, Europe’s Prize Bluffer,”

Dateline Toronto, E.B. White, ed. New York: Scribner’s Sons,1967, 253-59.

[6] Ernest Hemingway, In Our Time, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925

[7] Ibid.

Finding His Voice: Hemingway’s in our time, Part 2

In my first blog on Hemingway’s early book, in our time (1924) I wrote that the short vignettes within the book show how Hemingway’s distinctive voice was forming.

Where did that style come from? One profound influence was his work as a reporter for the Kansas City Star when he was 18. Though he only stayed seven months, the paper’s style guide—favoring short sentences, active verbs, and ruthless clarity—became the foundation of his literary voice. He later said it was “the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing.”

By Craig Mindrum

In my first blog [CM1] on Hemingway’s early book, in our time (1924) I wrote that the short vignettes within the book show how Hemingway’s distinctive voice was forming.

Where did that style come from? One profound influence was his work as a reporter for the Kansas City Star when he was 18. Though he only stayed seven months, the paper’s style guide—favoring short sentences, active verbs, and ruthless clarity—became the foundation of his literary voice. He later said it was “the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing.”

Hemingway also wrote for the Toronto Star and was sent to postwar Turkey and the Balkans as a foreign correspondent. He didn’t cover the fighting directly, but he witnessed the humanitarian disaster after the Turkish army recaptured Smyrna (İzmir). His dispatches from Constantinople and Thrace describe:

Refugee columns in retreat

Executions and forced deportations

The emotional numbness of survivors

These war impressions—fragmentary, unspeakable, raw—echo powerfully in the short, violent vignettes of in our time. This version doesn’t just preview Hemingway’s mature voice. It shows the intellectual and emotional labor of creating that voice.

Several of the vignettes deserve closer attention.

Chapter 6: The execution of six enemy cabinet ministers

Part of the horror of these stories comes from Hemingway telling us terrible events in a dispassionate voice. Here six Austrian military leaders are killed by firing squad in the middle of a rainstorm. One of the ministers was sick with typhoid and the soldiers could not get him to stand up, so he “sat down in a pool of water.” Finally the soldiers’ commanding officer “told the soldiers it was no good trying to make him stand up.” The story concludes abruptly: “When they fired the first volley he was sitting down in the water with his head on his knees.”

That being said, some of the sentences in this chapter read as if they were the parodies of Hemingway’s style that appeared after the author became famous:

There were wet dead leaves on the paving of the courtyard. It rained hard. All the shutters of the hospital were nailed shut.

In his more mature style, Hemingway knew how to mix these cold journalistic sentences with other forms of explication in a more rhythmic way that was slightly more pleasing to the ear.

Chapter 17: Another execution

This chapter describes the 1921 hanging of five men (including three Black men) for unknown crimes at six o’clock in the morning in Cook County jail in Chicago. One was Sam Cardinella, a Chicago mobster. They carried Cardinella out to the gallows and held him up. “When they came toward him with the cap to go over his head Sam Cardinella lost control of his sphincter muscle. The guards who had been holding him up dropped him. They were both disgusted.”

This is followed immediately by a bit of breezy chitchat by the men present. “’How about a chair, Will’ asked one of the guards, ‘Better get one,’ said a man in a derby hat.”

This detail packs a wallop by what Hemingway did not say: That here we have a supposedly upper-class man (who would have been wearing such a hat) observing the executions for sport. He’s an indifferent spectator, possibly representing polite society’s sanitized interest in public punishment.

This vignette continues Hemingway’s theme of death stripped of ceremony. There's no romanticism, no redemption — just the mechanical finality of execution. Cardinella is treated with almost clinical detachment, enhancing the emotional force of the scene.

Chapter 5: A parody of the aristocracy

This chapter opens with unusual language for Hemingway, filled with needless adjectives: “It was a frightfully hot day. We’d jammed an absolutely perfect barricade across the bridge.” And later, as they shot enemy soldiers trying to climb over, “It was absolutely topping.”

One might think Hemingway had suddenly become too expressive until one realizes this is not his narrative voice, but rather a deliberate parody of another voice — in this case, the affected, slang-laden banter of British soldiers reminiscing about colonial or wartime violence.

Hemingway mimics the cheerful, clipped idiom of British officers — the kind who might have served in colonial wars or World War I— casually describing executions or shootings in terms like “jolly good” and “what a lark.” The juxtaposition of this lighthearted tone with the horrifying content — killing helpless men — creates intense irony. The soldiers treat murder as sport.

The unusual use of adjectives like “jolly,” “awfully,” “perfectly topping” is not Hemingway losing control of his style. Rather, it’s him highlighting the obscenity of euphemistic language in the face of brutality. In these few lines, Hemingway skewers the self-satisfied narratives of imperial war-making. The casualness of the British voices emphasizes the moral numbness and inhumanity bred by long exposure to violence and power.

Because Hemingway does not editorialize, the reader has to do the moral work. He doesn’t say, “These men are monsters.” Instead, he lets their words reveal the dissonance. It’s a classic example of his “iceberg theory” — letting the horror float just beneath the surface.

Chapter 8: Empty promises

In this chapter, Hemingway describes a bombardment during which a man prays to be saved:

Oh jesus christ get me out of here. Dear jesus please get me out. Christ please please please christ. If you’ll only lee me from getting killed I’ll do anything you say. I believe in you and I’ll tell everyone in the world that you are the only thing that matters. Please please dear jesus.”

Though the next night “he did not tell the girl he went upstairs with at the Villa Rossa about Jesus. And he never told anybody.”

It’s brief, but like so many of Hemingway’s vignettes, it delivers a deep psychological and spiritual punch. Hemingway captures a universal and uncomfortable reality — the instinct to bargain with God in moments of crisis, only to discard those promises when safety returns. This isn’t just about a soldier; it’s about us.

The soldier’s plea is sincere in the moment, but it’s hollow — driven by fear, not transformation. There's an implicit critique of the shallow religiosity that surfaces in emergencies but fails to change behavior.

The final line — “And he never told anybody” — is devastating. It suggests a permanent rupture in the soldier’s moral life, possibly a symptom of trauma, cowardice, or the general corrosion of war. Unlike traditional religious narratives where the cry to Jesus leads to redemption, here it leads only to shame and self-deception. Grace is invoked but never received or honored.

*****

In an upcoming blog, Dr. Nancy Sindelar will write about the edition of In Our Time that was published the next year (1925), where the vignettes are woven into transitional pieces between his short stories.

Shadows: Hemingway’s “In Our Time,” Part 1

A strange book, containing the seeds of Hemingway’s mature style

What was Hemingway’s “first book”? Some confusion or disagreement exists in the biographical literature about which of Hemingway’s books came first.

By Craig Mindrum

A strange book, containing the seeds of Hemingway’s mature style

What was Hemingway’s “first book”? Some confusion or disagreement exists in the biographical literature about which of Hemingway’s books came first.

Technically speaking, his first published book was “Three Stories and Ten Poems,” published by Robert McAlmon, a central figure in the expatriate literary scene in Paris. McAlmon’s Contact Editions was known for publishing avant-garde and emerging modernist writers. At the time, Hemingway was just beginning to gain traction as a serious literary voice, and this 1923 collection helped get his name in circulation. It was a private printing of just a few hundred copies, so it isn’t mentioned as much. (Though it does contain “Up in Michigan,” his first serious attempt at fiction.

Often, people refer to In Our Time as his first book, published in 1925, which includes “Indian Camp,” “The Battler,” and “Big Two-Hearted River.”

Sandwiched in between those two, in 1924, a tiny Paris press released a slim, strange volume also called in our time (though using lowercase for the title), containing only a handful of page-long vignettes. No stories, no recurring characters, no clear arc—just flashes: executions, battlefield chaos, bullfights, arrests. It reads less like a narrative than echoes of narratives.

And yet, in these brief and brutal fragments, Hemingway’s revolutionary style was already beginning to form—tentative, experimental, and sometimes shocking.

A book of brevity and brutality

Published by Ezra Pound’s Three Mountains Press in an edition of just 170 copies, the 1924 in our time was part of modernist literature’s sharp break from traditional storytelling. Each piece is just a few paragraphs long, untitled, dropped without explanation into the reader’s hands. The scenes come and go without commentary, without extended plot, often without names.

Some have called these fragments prose poems. Hemingway likely would have rejected that label. But they are unmistakably poetic in the way they compress life into glinting shards. They offer no interpretation, no frame—just violence, distance, and the sound of boots on stone.

In a time when fiction still leaned heavily on exposition, in our time chose omission. It asked readers to do the work of feeling.

The voice begins to form

Despite its minimalism—or maybe because of it—this odd little book holds the DNA of Hemingway’s mature style. The clean nouns. The hard verbs. The moral weight carried by silence. You can feel him discovering the power of implication: that what’s left unsaid might be more important, even devastating, than what’s spelled out.

Some vignettes still land with shocking force. A soldier bleeds out in a German trench, his companion just alive enough to tell the dying soldier that “we’ve made a separate peace.” A matador is injured and then dies. Two Italians in Kansas City are shot and killed for no reason other than they are “wops.” These scenes leave an emotional bruise in just a few lines.

But other passages are clearly the work of a young writer trying things on—sometimes awkwardly, sometimes unsuccessfully.

It’s a record of a young writer figuring out what to say, how to say it, and, more importantly, how much not to say. These fragments are jagged, raw, sometimes deeply unsettling. They are the stripped wires of modernist fiction, humming with tension.

In their refusal to explain, they gesture toward trauma, guilt, failure, and the collapse of old orders. Hemingway didn’t yet have the stories to contain those themes. But he had the shadows.

Craig Mindrum, Ph.D., is a member of the Board of the Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park. He received his doctorate in an interdisciplinary field of ethics, theology, and literature from the University of Chicago. He is a writer and business consultant.