Shadows: Hemingway’s “In Our Time,” Part 1

By Craig Mindrum

A strange book, containing the seeds of Hemingway’s mature style

What was Hemingway’s “first book”? Some confusion or disagreement exists in the biographical literature about which of Hemingway’s books came first.

Technically speaking, his first published book was “Three Stories and Ten Poems,” published by Robert McAlmon, a central figure in the expatriate literary scene in Paris. McAlmon’s Contact Editions was known for publishing avant-garde and emerging modernist writers. At the time, Hemingway was just beginning to gain traction as a serious literary voice, and this 1923 collection helped get his name in circulation. It was a private printing of just a few hundred copies, so it isn’t mentioned as much. (Though it does contain “Up in Michigan,” his first serious attempt at fiction.

Often, people refer to In Our Time as his first book, published in 1925, which includes “Indian Camp,” “The Battler,” and “Big Two-Hearted River.”

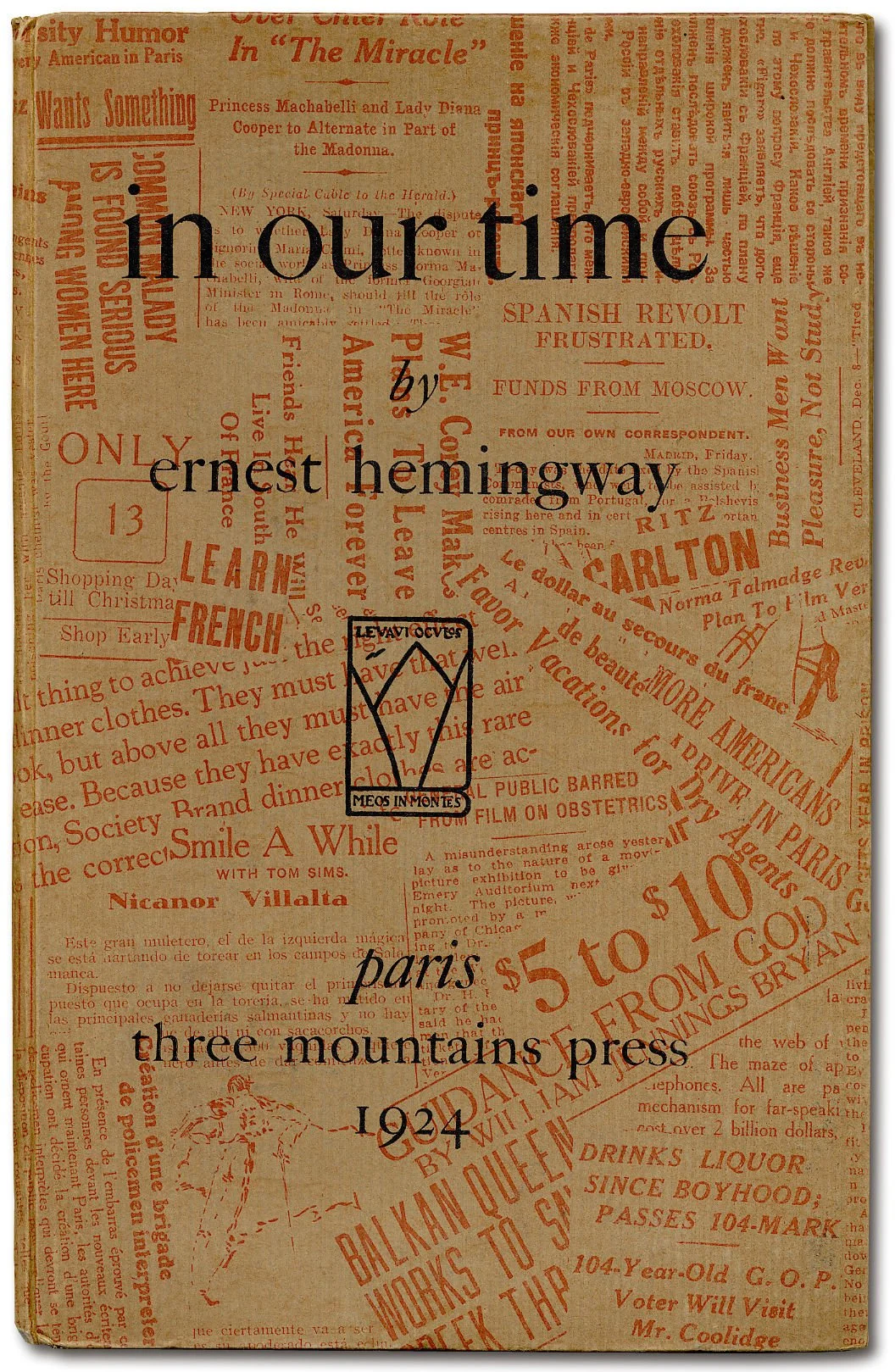

Sandwiched in between those two, in 1924, a tiny Paris press released a slim, strange volume also called in our time (though using lowercase for the title), containing only a handful of page-long vignettes. No stories, no recurring characters, no clear arc—just flashes: executions, battlefield chaos, bullfights, arrests. It reads less like a narrative than echoes of narratives.

And yet, in these brief and brutal fragments, Hemingway’s revolutionary style was already beginning to form—tentative, experimental, and sometimes shocking.

A book of brevity and brutality

Published by Ezra Pound’s Three Mountains Press in an edition of just 170 copies, the 1924 in our time was part of modernist literature’s sharp break from traditional storytelling. Each piece is just a few paragraphs long, untitled, dropped without explanation into the reader’s hands. The scenes come and go without commentary, without extended plot, often without names.

Some have called these fragments prose poems. Hemingway likely would have rejected that label. But they are unmistakably poetic in the way they compress life into glinting shards. They offer no interpretation, no frame—just violence, distance, and the sound of boots on stone.

In a time when fiction still leaned heavily on exposition, in our time chose omission. It asked readers to do the work of feeling.

The voice begins to form

Despite its minimalism—or maybe because of it—this odd little book holds the DNA of Hemingway’s mature style. The clean nouns. The hard verbs. The moral weight carried by silence. You can feel him discovering the power of implication: that what’s left unsaid might be more important, even devastating, than what’s spelled out.

Some vignettes still land with shocking force. A soldier bleeds out in a German trench, his companion just alive enough to tell the dying soldier that “we’ve made a separate peace.” A matador is injured and then dies. Two Italians in Kansas City are shot and killed for no reason other than they are “wops.” These scenes leave an emotional bruise in just a few lines.

But other passages are clearly the work of a young writer trying things on—sometimes awkwardly, sometimes unsuccessfully.

It’s a record of a young writer figuring out what to say, how to say it, and, more importantly, how much not to say. These fragments are jagged, raw, sometimes deeply unsettling. They are the stripped wires of modernist fiction, humming with tension.

In their refusal to explain, they gesture toward trauma, guilt, failure, and the collapse of old orders. Hemingway didn’t yet have the stories to contain those themes. But he had the shadows.

Craig Mindrum, Ph.D., is a member of the Board of the Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park. He received his doctorate in an interdisciplinary field of ethics, theology, and literature from the University of Chicago. He is a writer and business consultant.