A MOVEABLE READ BLOG

This section of the website serves as a journal space for ongoing discussions on a variety of subjects but not limited to, Hemingway, literature, and the arts. Authors both named and possibly unnamed will post all manner of topics and discussions. Please note while the Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park (EHFOP) will moderate this page, it does not mean that we condone or sanction any specific viewpoint. If you are interested in posting to the page, please contact us HERE with specifics and we will advise on next steps for possible publication on our site.

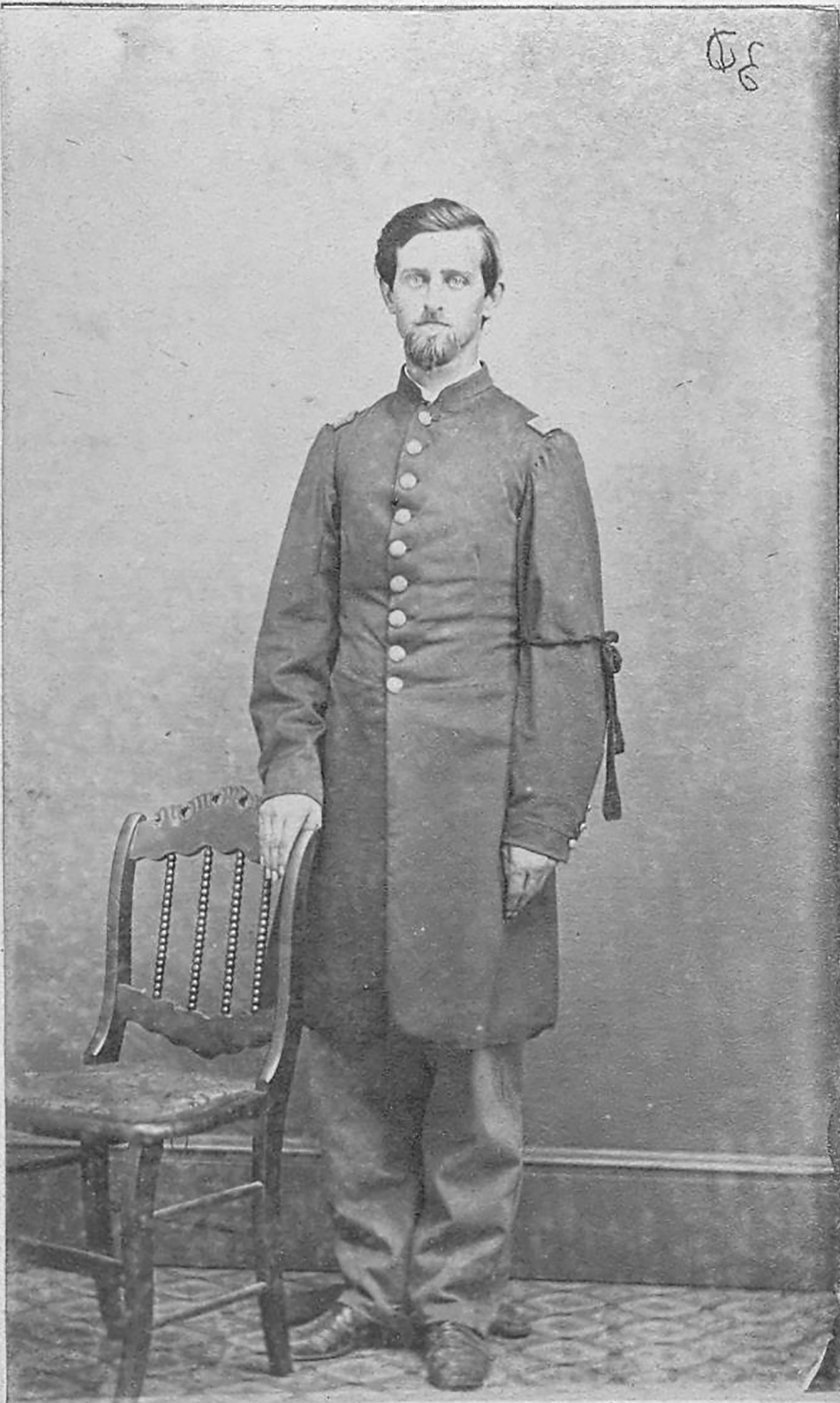

On January 1, 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. By that date Allen and Harriet Louisa Tyler Hemingway, recent transplants from Connecticut to Illinois, had already buried one son and had two other sons serving in the Union Army.

In the closing years of World War I, 1917-1918, hundreds of American libraries, under an initiative of the American Library Association (ALA), launched the Library War Service, a project to send books to the doughboys fighting in the trenches. By the Armistice, nearly a million and a half books had been shipped to Europe.

In 1917, while a senior at Oak Park High School, Hemingway got into a bit of trouble. He and some buddies got together and published an underground magazine called “Jazz Journal.” In the 1910s, “jazz” was by itself a suggestive word, carrying modern, even scandalous connotations (nightlife, sexual looseness).

He was sitting at the next table, a tall fat young man with spectacles. He had ordered a beer. I thought I would ignore him and see if I could write. So I ignored him and wrote two sentences.

Speaking of Willa Cather, can anyone of our readers place this Hemingway quote? (Noting his bumping iambs, his simple declarative clauses, his monosyllabic repetitions, and the Bachian musicality in “made me bite my tongue,” “When the straw settled down,” or “from under the buffalo hide.”)

As the Director of the English Honors Program here at Western Kentucky University, I developed a course entitled “Honors Hemingway and Faulkner,” and I have taught this class each fall for over a decade.

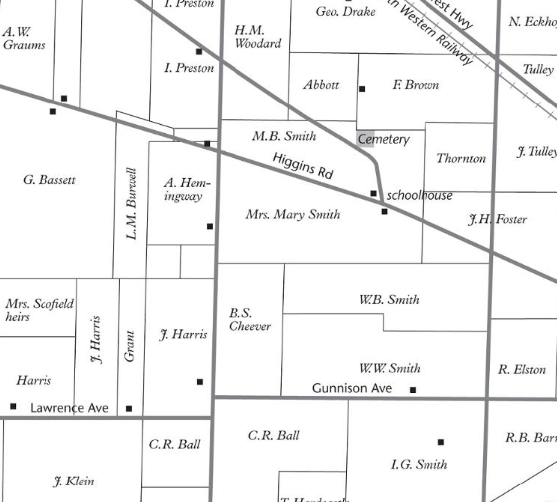

It was a pleasant Wendy's. I ordered a cup of coffee and took it out front to a cement table, just feet from gridlocked Harlem Avenue. Next door, cars rolled in and out of a Shell station at the corner of Higgins Road in northeast Illinois. To the West, stacks of empty balconies fronted a series of tall, brick apartment buildings. Thunderous Kennedy expressway traffic roared past in a gulch 200 feet to the north. I had arrived at the farm of Ernest Hemingway’s great-grandfather.

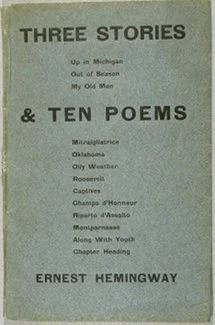

To wrap up our discussion of his earliest writing, I’m going to take a look at Three Stories and Ten Poems, his official first book (1923). I’ll focus on two of the three stories in the book, then discuss some of his poems.

Ernest Hemingway published In Our Time in 1925, a year when people still were reeling from the impact of World War I. Hemingway and others had believed World War I was going to be the war to end all wars but quickly learned it was a futile blood bath. There were no heroes—just passive victims hit by shells in trenches, poisoned with gas, or scorched by flame-throwers.

In my first blog on Hemingway’s early book, in our time (1924) I wrote that the short vignettes within the book show how Hemingway’s distinctive voice was forming.

Where did that style come from? One profound influence was his work as a reporter for the Kansas City Star when he was 18. Though he only stayed seven months, the paper’s style guide—favoring short sentences, active verbs, and ruthless clarity—became the foundation of his literary voice. He later said it was “the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing.”