Hemingway shows his promise as a writer: Three Stories and Ten Poems

By Craig Mindrum, Ph.D.

In previous blogs, we have focused on Hemingway’s early years as a writer. In two blogs[1], we discussed in our time, a series of powerful vignettes about war and the threat of death, published in 1923. We then looked at [2] his 1924 edition of In Our Time, where the vignettes are used as interchapters between some excellent early stories.

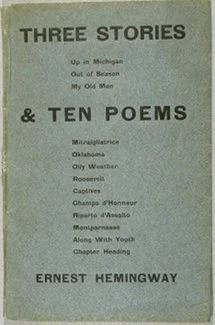

To wrap up our discussion of his earliest writing, I’m going to take a look at Three Stories and Ten Poems, his official first book (1923). I’ll focus on two of the three stories in the book, then discuss some of his poems.

“Up in Michigan”

In Hemingway’s early story “Up in Michigan,” the quiet longing of a young woman turns abruptly into a harrowing scene of sexual violence. Liz Coates, a waitress in the small town of Hortons Bay, Michigan, develops a romantic infatuation with Jim Gilmore, a local blacksmith. One evening, after a dinner with friends and too much to drink, Jim takes Liz for a walk and then assaults her on a cold dock, ignoring her resistance. The scene is brief but brutal, rendered in Hemingway’s early minimalist style, which makes the violence feel all the more stark.

Jim puts his hand on Liz’s leg and starts to move up. “Don’t, Jim,” she says. “You mustn’t Jim, you mustn’t.” He pays no attention to her.

The boards were hard. Jim had her dress up and was trying to do something to her. She was frightened but she wanted it. She had to have it but it frightened her.

“You mustn't do it Jim. You mustn't.”

“I got to. I'm going to. You know we got to.”

“No we haven't Jim. We ain't got to. Oh it isn't right. Oh it's so big and it hurts so. You can't. Oh Jim. Jim. Oh.”

When Three Stories and Ten Poems was first published in 1923, the story received little attention, largely because it was printed in a small edition by a Paris avant-garde press. But when Hemingway tried to reintroduce the story to American readers, publishers objected. His editor at Scribner’s, Maxwell Perkins, refused to include it in collections for years. A century later, readers approach the same scene with more clarity about consent and trauma.

What once passed as a story of “rough passion” is now unmistakably identified as rape. The unknown narrator of Hemingway’s story is silent about Liz’s suffering, which raises uncomfortable questions. The story remains powerful, but today it demands to be read not only as literature, but as a reflection of gendered violence—and the cultural blind spots that long protected it.

One can feel justified anger at how Hemingway handles the aftermath of the rape, where he undermines the trauma of the event. Liz has trouble extricating herself from under Jim, who has passed out. She wiggles free, then ends up placing her coat over him to keep him warm. She tucks the coat around him. She kisses his cheek.

“Out of Season”

“Out of Season” is an oblique and difficult story. Even here, early in his career, Hemingway leaves much unsaid, forcing the reader to fill in the blanks. It appears to be, in the end, a story of marital discontent and malaise. Nothing goes right (one meaning of the title—recall Hamlet: (“The season is out of joint”).

The story is set in Italy and follows an American couple—referred to only as the young gentleman (sometimes just “y.g.”) and his wife—as they set out on a fishing trip on a cold day led by a local, Peduzzi, a drunken and slightly pathetic guide. The couple and Peduzzi walk through the town and out into the countryside toward the stream where they plan to fish, but the trip is disorganized and strange from the start. Peduzzi doesn’t have a fishing permit (a real source of concern for the young couple), doesn’t know where to get bait, and doesn’t have the right equipment.

The wife becomes increasingly irritated and eventually turns back, leaving the young man and Peduzzi to continue. When they finally reach the stream, they find it too high and fast to fish. The story ends with a moment of vague despair. Peduzzi wants to fish again in the morning, but the young gentleman (who has bankrolled Peduzzi’s drinking throughout the day) indicates he will not be joining them the next day. Attending to his marriage may be his motive.

The couple’s attempt at a leisure activity—fishing—may be a sign of trying to bridge the gap between them, but it fails miserably. The American couple and the Italian guide can’t communicate well, and the result is a series of small failures and embarrassments. The awkwardness of cross-cultural interaction is used to explore the couple’s own inability to communicate.

The season is wrong for fishing, the cold day mirrors the marriage, and the human connections are out of sync. Like much of Hemingway’s work, the story refuses easy resolution.

The Poems

The ten poems in Three Stories and Ten Poems range from shallow exercises to a few surprisingly mature pieces that hint at Hemingway’s emerging voice. The standout is “Champs d’Honneur” (“Fields of Honor”), a biting indictment of anonymous war that distills Hemingway’s postwar cynicism:

Soldiers never do die well;

Crosses mark the places—

Wooden crosses where they fell,

Stuck above their faces.

Soldiers pitch and cough and twitch—

all the world roars red and black;

Soldiers smother in a ditch,

Choking through the whole attack.

I admire the rhymes here—a kind of rhetorical order undermined by the disorder and horror described in the poem. It also includes effective alliteration and off-rhyming: “pitch and cough and twitch.”

“Riparto d’Assalto” (“Assault Unit”) includes what I would term immature and tentative use of repetition and rhyme. But it has its merits. The poem is more subdued than “Champs d’Honneur,” but just as affecting—a terse portrait of soldiers as pawns, advancing toward death with no names and no heroics, only cold inevitability.

In “Montparnasse” (a neighborhood in Paris famous for being a hub of artists, poets, and expatriates in the 1920s) Hemingway turns his attention to the bohemian world of Paris, capturing the psychological detachment of expatriates and artists who circle around death and disillusionment with a practiced cool.

These poems are not perfect, but they reveal a young writer already rejecting sentimentality and testing the emotional compression that would become his hallmark. The rest of the poems—ranging from crass (“Oklahoma”) to aimless or overwritten (“Ultimately,” “The Soul of Spain”)—serve mostly to remind us that Hemingway’s use of spare, precise language was hard-won.