Farming in Hemingway’s Family

By Eric Kammerer

“It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait." Ernest Hemingway - A Moveable Feast

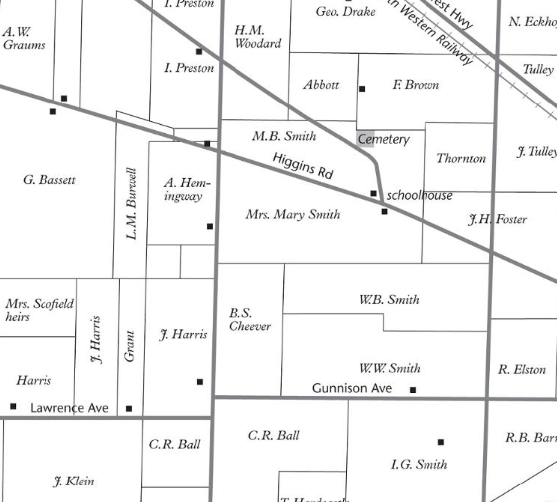

It was a pleasant Wendy's. I ordered a cup of coffee and took it out front to a cement table, just feet from gridlocked Harlem Avenue. Next door, cars rolled in and out of a Shell station at the corner of Higgins Road in northeast Illinois. To the West, stacks of empty balconies fronted a series of tall, brick apartment buildings. Thunderous Kennedy expressway traffic roared past in a gulch 200 feet to the north. I had arrived at the farm of Ernest Hemingway’s great-grandfather.

Allen Hemingway (1808-1886) was Ernest Hemingway's paternal great-grandfather. He arrived in Illinois in 1854,[1] settling on 80 acres in the outlying rural community of Leyden,[2] northwest of Chicago. His farm was in what is now Chicago's Oriole Park neighborhood, part of the Norwood Park community area. He came from Terryville, Connecticut, where he served as postmaster[3] and owned a general store.[4]

More than 70 years later, Allen's youngest son, Anson, claimed the move was motivated by his father's failing health.[5] If so, his dad chose a strenuous new lifestyle, as a combination farmer and commuting merchant, with a side gig as a Sunday school teacher.

A new railroad

The Illinois and Wisconsin Railroad was completed through Leyden in 1853. This new transportation option allowed Allen, undoubtedly after leaving a long chore list for his three sons, to travel into Chicago to operate his wholesale clock store, located on Clark Street below the offices of the fledgling Chicago Tribune.[6] The Seth Thomas Clock Company was incorporated in 1853 near where the Hemingways had lived in Connecticut, so Allen likely had connections in the timepiece business.

Leaving a legacy

But the move may also have been prompted by a desire to leave a legacy of land. As his second wife wrote: "Mr. Hemingway is quite engaged about going out West to buy a farm for his boys. . ."[7] This dream would be dashed by the Civil War, when disease killed his two oldest sons, Union Army soldiers. Anson, Ernest Hemingway's grandfather, would go on to a long life after his Civil War service, working for the YMCA and then in real estate.

Ernest and farming

Ernest Hemingway was no stranger to farms. His parents put him to work on their forty-acre patch, which they dubbed Longmont, after a farm in their favorite Victorian novel. Longmont was across the lake from Windemere, the Hemingway’s summer home in Michigan. The family began spending summers there around 1899, the year Ernest was born. They returned nearly every summer during his childhood and teenage years, well into the 1910s.

Ernest developed an aversion to digging potatoes and picking fruit. The situation sowed seeds of adolescent rebellion, which would cause bitter conflicts with his parents.[8] Ernest shared the attitude of his maternal grandfather, Ernest Hall, toward farm work. Marcelline Hemingway reported that Hall said he "hated" it.[9]

Moving between two worlds

Allen Hemingway moved daily between two eras: building a tranquil country home for his boys while riding the train downtown to work in "a rough, vulgar town that seemed to wallow in its own love of money and increasing commercialism."[10]

Chicago’s population exploded 300% between 1850 and 1860 to 112,000. The city grew due to an increasing role as a rail hub, and the Illinois and Michigan Canal opening a route to the Mississippi.[11]

Ernest Hemingway, who emerged from a proper Victorian household to post-war disillusionment, also moved between eras personally and artistically. Back in Chicago at age 20, he "wanted to be seen in exile from the banal Midwest and unencumbered by family, business, and money concerns."[12]

From farms to car washes

At the corner of Harlem Avenue and Higgins Road, the land that used to be Allen Hemingway's farm now features gasoline, car washes, and Baconators™. The convenience store in the gas station sells everyday necessities, just like Allen Hemingway's store in Connecticut.

While you're in the area, consider visiting the Norwood Park Historical Society, where exhibits show an evolution from pioneer farming settlement, to independent 19th-century railroad suburb, to city neighborhood. You can also visit Allen Hemingway's gravesite in Union Ridge Cemetery. You can get a great cup of coffee at October Cafe.

Hemingway’s birthplace home

Four short miles away, you can enter the Victorian era by touring Ernest Hemingway's birthplace home (https://www.hemingwaybirthplace.com/) in Oak Park, Illinois.

Eric Kammerer is a volunteer docent at the Ernest Hemingway Birthplace Museum. He is a writer from the western suburbs of Chicago.

[1] Hemingway, P. S. (1988). The Hemingways: Past & present and allied families. Gateway Press.

[2] Conzen, Michael P. and Keating, Ann Durkin. (2005). Land Subdivision and Urbanization on Chicago’s Northwest Side. Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved at http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1754.html

[3] Litchfield County Postmasters, retrieved at https://www.cga.ct.gov/hco/img/history/norton/LitchfieldPostmasters.pdf

[4] Taylor, William Harrison. (1890) Taylor’s Souvenir of the Capitol.

[5] Anson T. Hemingway, Early Settler Celebrates his Eighty-Second Birthday Anniversary -- Recalls Memories of Days That Are Gone. (1926, August 28). Oak Leaves.

[6] Hemingway, P.S.

[7] Nagel, James. (1996). Ernest Hemingway: The Oak Park Legacy. University of Alabama Press.

[8] Dearborn, Mary V. (2017). Ernest Hemingway: A Biography. Vintage Books.

[9] Sanford, Marcelline Sanford. (1962) At the Hemingways. University of Idaho Press.

[10] Moore, Michelle E. (2019). Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Bloomsbury Academic

[11] Bross, W. (1876). History of Chicago: historical and commercial statistics, sketches, facts and figures, republished from the "Daily Democratic press" ; What I remember of early Chicago, a lecture, delivered in McCormick's hall, January 23, 1876 (Tribune, January 24th). Chicago: Jansen, McClurg & Co..

[12] Ibid.

*1861 Development Map of Norwood Park Area, courtesy of the Newberry Library

**photo credit, exhibit at the Norwood Park Historical Society